Bowling News, Radical Bowling Ball Videos

One Man’s Amazing Journey to the Center of the Bowling Ball

Mo Pinel spent a career reshaping the ball’s inner core to harness the power of physics. He revolutionized the sport—and spared no critics along the way.

THE SWEET CLANG of scattering pins echoed through Western Bowl, a cavernous 68-lane bowling alley on the edge of Cincinnati. It was day one of the 1993 Super Hoinke

A Thanksgiving weekend tournament that drew hundreds of the nation’s top amateurs—teachers, accountants, and truck drivers who excelled at the art of scoring strikes. They came to the Super Hoinke (“HOING-key”) to vie for a $100,000 grand prize and bowling-world fame.

Between games, many bowlers drifted to the alley’s pro shop to soak in the wisdom of Maurice “Mo” Pinel, a star ball designer for the sporting-goods giant AMF. Pinel had come to Cincinnati to promote his latest creation, the Sumo. The bowling ball had launched the year before, backed by a TV commercial featuring a ginormous Japanese wrestler bellyflopping down a lane, with the tagline “Flat out, more power than you’ve ever seen in a bowling center.” The ball had quickly become a sensation, hailed for the way it naturally darted sideways across the lane—a quality known as flare. To congratulate Pinel on the sale of the 100,000th Sumo, AMF had given him a chunky medallion embossed with writing in kanji, a bauble that dangled from his neck as he held court at the Super Hoinke.

The paunchy, shaggy-haired Pinel spent hours regaling the pro-shop crowd with his opinions on the Sumo and all things ball-related. His blunt commentary, delivered in the thick Brooklynese of his youth, ranged from the correct technique for drilling finger holes to his rival designers’ failure to appreciate Newton’s second law. The audience lapped up his acerbic takes on how to improve the sport’s most essential piece of equipment.

Fifteen-year-old Ronald Hickland Jr. was among the enthralled. A gifted math and science student who was falling in love with bowling, Hickland was captivated by Pinel’s zest for breaking down the technical minutiae of why balls roll the way they do. He was equally impressed by the flashiness of Pinel’s jewelry: In addition to the gaudy kanji necklace, Pinel sported a top-of-the-line Movado wristwatch—a luxury he was able to afford thanks to the $3-per-ball royalty he was getting from AMF.

Hickland had traveled from Indiana to cheer on his dad at the Super Hoinke. Listening to Pinel, he found his calling in life. “It was like lightning,” he recalls. “And I was like, well, how do I get your job when I grow up?”

Pinel cautioned the teenager that the road ahead would be difficult. He would first have to earn a degree in mechanical or chemical engineering, after which he’d need vast amounts of persistence and luck: The number of full-time bowling ball designers in the world could be counted on two hands.

more bowling article you may enjoy

Hickland took that advice to heart, and he would eventually become one of the fortunate few to carve out a long career in ball design. He knows many would dismiss his chosen profession as frivolous. Bowling is easy to shrug off as a mere leisure pursuit—a boozy weekend pastime in which anyone with decent hand-eye coordination can perform well enough. But hardcore bowlers have a very different take on the sport: To them it’s a physics puzzle so elaborate that it can never be mastered, no matter how many thousands of hours they spend pondering the variables that can ruin a ball’s 60-foot journey to the pins. The athletes who obsess over this complexity also understand the debt they owe to Pinel, whose career as a ball designer was just beginning when he attended the Super Hoinke in 1993. Notorious as a bit of a colorful crank, he is also the figure most responsible for transforming how bowlers think about the scientific limits of their sport.

IN THE EARLY days of the pandemic, when ambulance sirens wailed nonstop in my hard-hit Queens, New York, neighborhood, I often soothed myself by bingeing YouTube clips of bowling. I can’t remember how I first plunged down that rabbit hole, though it might have involved clicking a “Recommended for You” video in the sidebar next to the Jesus Quintana scene from The Big Lebowski. My personal experience with bowling amounted to little more than a few madcap nights with friends, yet I devoured hours’ worth of highlights from professional matches, marveling at the athletes’ ability to arc their shots with such precision. Flair atop flare. There was something hypnotic about the physics of the balls’ movement, how those sleek orbs danced along the gutters before gracefully breaking toward the pins as if nudged by unseen hands.

Gorging on this content piqued my curiosity about the role a ball’s physical properties play in determining the outcome of each shot. A bowler’s prowess is clearly what matters most, but I assumed the composition of the balls must factor into the equation—arguably more so than in any other sport, given bowling’s simplicity. I became keen to learn how bowling balls are constructed and how much of an edge a bowler can glean by using a ball that’s been tailored to enhance their skills.

Grasping the basics of ball design turned out to be more complicated than I’d imagined. When I waded into the archives of Bowling This Month to study the magazine’s ball reviews, I was overwhelmed by nearly a thousand detailed evaluations, each peppered with jargon: “radius of gyration,” “positive axis point,” “mass bias location.” And up to a dozen new balls are released each month, almost all claiming to represent technological breakthroughs that will revolutionize the sport. The promotional copy for Storm Bowling’s Parallax Effect, a ball that debuted in March, offers a typically impenetrable boast: “The strategically positioned depressions on the Z-axis 6-¾” from the pin mimic the effect of an extra hole in a similar space and keeps the intermediate differential at a more workable amount.”

My bowling-ball education might have stalled early on were it not for the cutaway diagrams included in most spec sheets. These illustrations reveal the hidden guts of balls, showing a dazzling assortment of shapes and sizes. Unlike baseballs and golf balls, which are built around spherical cores, bowling balls contain cores that defy easy description: They can bear vague resemblance to gas masks, hand grenades, guitar bodies, Easter Island statues, Rorschach ink blots.

When I looked into the scientific reasons these cores are so strangely shaped, the name Mo Pinel kept popping up. He was widely credited as the designer who’d sparked the proliferation of funky cores in the early to mid-1990s, and at the age of 78 he was still espousing his theories as the technology director for Radical Bowling, a ball manufacturer that prides itself on catering to “geeks, physicists, and performance junkies.” His primary venue for reaching bowlers online was his weekly YouTube series, #MoMonday, in which he often uses a dry-erase board to elucidate the arcana of ball behavior.

Pinel struck me as the ideal Virgil to guide me through the nuances of bowling ball design. But when he failed to return several of my emails and voicemails, I feared he might be too much of a curmudgeon to help an outsider like me. The persona he conveys on YouTube can charitably be described as gruff, and his acquaintances confirmed my hunch that Pinel could be a prickly sort. “Mo, if he doesn’t like you, he’s not going to spend any time or anything with you,” says Neil Stremmel, a former executive at the United States Bowling Congress, the sport’s governing body, who now manages an alley in central Florida. “He won’t go out of his way to be a jerk or make a fool out of you, but he won’t spend any of his time with you.”

I was delighted, then, when Pinel finally gave me a ring in late January, right as I was about to give up on my project. He said he’d never received my emails, perhaps because—despite his job title at Radical—he’s fairly computer-averse. (“I had to have someone turn it on for me,” he half jokes.) He’d been slow to reply to my phone calls in part because he’d been waiting for a coworker to vet my credentials, but also because he was so busy. He had recently left his home in Virginia, where he lives with his wife of nearly 10 years, to embark on an extended driving tour of southern bowling alleys. Though the pandemic was just past its peak in the US, he was spending the next two months teaching pro-shop employees how to match clients to their ideal balls.

Over the next few weeks, as Pinel trekked across Georgia and Florida, we chatted on the phone about the finer points of bowling ball design. It turned out Mo could indeed turn cantankerous when I asked questions that betrayed my ignorance, and he’d press me to read a slew of complex documents before we spoke again. But I didn’t mind Pinel’s fits of crankiness, because I was so moved by the joy he exuded when sharing his bowling ball knowledge—an intellectual treasure that took him a lifetime to amass.

A former drag racer, Pinel didn’t fully embark on his legendary ball design career until he was nearing his 50s. PHOTOGRAPH: ELIZABETH RENSTROM; PORTRAIT COURTESY OF MONICA WESTFALL-PINEL

PINEL GREW UP in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, in a household that he describes as “technically oriented.” His father was a patent attorney at the International Nickel Company, where he handled the paperwork for inventions such as a method for iridium plating and a new type of slide rule. Pinel was bright enough to get into Cornell University, where he earned a degree in chemical engineering, but he had no intention of following in his dad’s footsteps. Rather than step onto a corporate ladder after graduation, he hung around his college town of Ithaca, New York, and got heavy into drag racing. When not tinkering with hot-rod engines, he could usually be found on a tennis court, hustling lesser players for pocket money.

After narrowly surviving two wrecks at a drag strip, Pinel thought it wise to find a safer way to satisfy his yen for competition. So he made the switch to bowling in 1969. He came to view the pastime as a spiritual cousin to drag racing: Both involve a few seconds of precise and rapid travel down a narrow path, and both appeal to those who relish technical conundrums. “A bowling ball is just a gyroscope that’s not on its preferred spin axis, right?” Pinel says when trying to describe his affection for the sport. “So ball motion is one gyroscope operating in the field of a bigger gyroscope, which is the earth.”

Pinel quickly taught himself the game well enough to win small purses at regional tournaments. He soon began to wonder whether he could reach the sport’s next tier by hacking his equipment. His main aim was to tease more flare potential out of a ball—in essence, reconfigure it to create a sharper hooking motion. That hook is essential because of how the sport’s pins are arrayed. There is an inches-wide “pocket” on either side of the front pin that all bowlers aim to hit at the optimum entry angle; if they manage to do so, they have a 95 percent chance of scoring a strike.

When Pinel looked into the discourse around ball performance, he found that most everyone believed that all that mattered was the quality of coverstock—that is, the exterior layer of a ball that is visible to the naked eye. Coverstocks are studded with microscopic spikes, the roughness of which is measured by the average distance from each spike’s peak to valley—a metric known as Ra. The higher a ball’s Ra, the more friction it can create with the lane and thus the greater the potential that it will hook well under the right circumstances. The hardness of the material that underlies the spikes is also an important factor. In the early 1970s, several pros had enjoyed great success by soaking their balls in methyl ethyl ketone, a flammable solvent that softened the coverstocks. (The balls became so gelatinous, in fact, that a bowler could indent the surface with a fingernail.) These softer balls gripped the lane much better than their harder counterparts, and so they tended not to skid unpredictably when encountering patches of oil used to dress the wooden boards. The use of methyl ethyl ketone had increased scores so much that rules were put in place mandating a degree of coverstock hardness as measured by a device known as a Shore durometer.

Pinel thought that too much attention was being paid to coverstocks and not nearly enough to what was inside the ball. The hearts of bowling balls, he discovered, were virtually all the same. Each had a round and centered core topped by a pancake-shaped weight block. Based on his experiences with drag racing, a sport in which the engine is every bit as important as the tires, Pinel figured he could change a ball’s dynamics by tweaking its internal structure.

He started to conduct experiments at an Ithaca pro shop where he knew the manager. Pinel used the shop’s drill and off-the-shelf components to alter balls. He’d pock them with deep holes that he’d then fill with dense wads of barium, a soft metal. “So I’d drill a hole, fill it with either dense or light stuff, and plug it to the top,” he says. “And I started playing around with that, and I started to see some differences in motion.”

Never lacking confidence, Pinel contacted several ball manufacturers in 1973 and proposed a deal: If they would sign a nondisclosure agreement, he’d brief them on his experimental results and help them design balls that would allow amateurs and pros alike to increase their strike rates. Company executives responded that they were willing to listen to Pinel’s ideas, but he was the one who would have to sign a release affirming that nothing he said was confidential. Miffed by what he saw as attempts to steal his ideas, Pinel veered away from a career in ball design.

Pinel continued to bowl in mid-size pro tournaments for a few more years, but he was never good enough to make a splash on the national scene. After getting into a bad car accident, he shifted into the business side of bowling. He cofounded a lane-resurfacing company, Resurfaced by Us, and ran an alley in New York’s Mohawk Valley. Through the spring and summer months, Pinel traveled constantly for the resurfacing company, spending post-work nights chewing the fat with fellow bowling nerds. After a few cocktails, the conversation would often turn to the physics of bowling balls, and Pinel would sketch out ideas for novel cores on bar napkins. But there seemed to be no feasible way for him to execute his visions.

As he approached his 50th birthday, Pinel decided to take one last stab at becoming a bona fide ball designer: He set out to make a ball that would change the sport by reliably flaring into the pins.

To accomplish this, he had to tinker with a specification known as radius of gyration, or RG. Put simply, RG is a measurement of the distance between the ball’s center of mass and the tip of the invisible axis that extends to the ball’s surface. (The technical definition: “The square root of the moment of inertia divided by the mass of the object.”) The lower a ball’s RG, the more spin a bowler can create by applying torque; the higher the RG, the more power required to rotate the ball. The most common analogy that ball designers use is that of a spinning figure skater, who can slow down their speed by extending their arms away from their center of mass.

Every ball has a narrow range of different RGs, based on how the ball is manufactured and where the finger holes are drilled; if a ball is rolling directly over the finger holes, for example, its axis of rotation, and thus its RG, will be on the smaller side. Pinel’s hypothesis, based on intuition and his layman’s grasp of physics, was that by creating cores that were asymmetric—that is, which move the center of mass closer to a ball’s surface—he would nudge up the ratio between a ball’s maximum and minimum RG. He believed this would cause a ball to exhibit an organic wobble that would bend it toward the pins over the final third of a lane—sort of like how the edges of a spinning top dip toward the ground as its inertia slows.

Pinel drew up a variety of designs for asymmetric ball cores, then, in April 1990, filed a patent for his favorite. It was a bulbous hunk of polyester with both a central indention and a conic tail, and portions of it resembled the sides of an octagon. (The best visual analogy may be a top-down view of Master Chief’s helmet in the video game Halo, but that’s a gross oversimplification.) The purpose of all this weirdness, as Pinel wrote in his patent application, was to make the ball’s motion volatile by design: “By utilizing different masses and/or dimensions for the head and tip portions, an asymmetrical weight distribution about the roll axis of the ball can be developed.”

Shortly after submitting his patent, Pinel received a call from Phil Cardinale, whom he knew from his business travels for Resurfaced by Us. A financial analyst from Long Island who moonlighted as a ball driller in a pro shop, Cardinale passed along some odd yet exciting news: Through a labyrinthine series of events, he’d been hired to revive a financially troubled ball brand called Star Traxx, which he had renamed Track. He recalled Pinel’s napkin sketches of unorthodox cores and invited him to help design a new Track ball. It was a one-time chance to test out whether his theories would hold up in the real world.

Pinel seized the opportunity. He created a core based on the “tip-and-tail” concept he’d just applied to patent. The resulting ball, the Shark, flared even when a bowler didn’t apply much spin at the moment of release. It was an innovation that caught the eye of the bowling division at AMF, which poached Pinel with the promise of a healthy royalty for each ball sold.

The AMF Sumo, the smash-hit ball that would earn Pinel his kanji pendant, was released in 1992. This time, Pinel opted for a core that bears a passing resemblance to the video game character Q*Bert, albeit with a disc at the base in lieu of feet. The ball came out right as new regulations called for more oil to be poured on lanes, a change that decreased friction; this sapped shots of spin and power. The extra oil was no match for the Sumo, however, because Pinel’s core caused it to slice hard across the boards near the pins. The ball would eventually sell well enough to make Pinel a modestly wealthy man.

Pinel says the size of his royalty eventually became a problem for AMF, and the company terminated his contract in 1995. He was barely out of work a week before he was hired by Faball, a struggling manufacturer in Baltimore. Pinel toured Faball’s factory and examined a freshly made core that the company used in its Hammer brand. It had a symmetrical and unexciting shape—the center looked like a lemon, and there were two convex caps of equal size on either side. In a moment that has now passed into ball-design legend, Pinel grabbed the core, which was still soft because the polyester had yet to cure, and sliced off the ends with a palette knife. Then he smooshed the caps back on into positions that were slightly askew, so that the contraption now looked like a Y-wing fighter from Star Wars.

The ball that contained this revamped core, the Hammer 3D Offset, would become Pinel’s signature achievement. “That ball sold like hotcakes for three years, where the average life span of a ball was about six months,” says Del Warren, a former ball designer who now works as a coach in Florida. “They literally couldn’t build enough of them.” In addition to flaring like few other balls on the market, the 3D Offset was idiot-proof: The core was designed in such a way that it would be hard for a pro shop to muck up its action by drilling a customer’s finger holes incorrectly, an innovation that made bowlers less nervous about plunking down $200 for a ball.

“What he did was he helped to bring asymmetry into a better understanding,” says Ronald Hickland, the teenage Pinel fan who went on to design more than 400 balls for Ebonite International. “He had a good way of marketing those balls and those shapes to get people to begin to understand. And so I think a lot of the current philosophies around asymmetry, he was influential in helping to explain that to the consumer.”

Pinel was delighted by the 3D Offset’s success not just because it affirmed his beliefs about the importance of asymmetry but also because it inflicted pain on his former employer. “AMF had been doing $12 million a year; Hammer had been doing $1 million,” he told me. “When we came out with the 3D Offset, Hammer did $12 million a year and AMF did $1 million. Not that I enjoyed that at all.” AMF would file for bankruptcy four years later.

WITH HIS REPUTATION at its zenith after the success of the 3D Offset, Pinel decided—at the age of 57—to become a bowling ball entrepreneur. In 1999, he and his partner from Resurfaced by Us joined forces to launch a Virginia-based ball-manufacturing startup called MoRich. They aimed to produce an ever more daring series of asymmetric balls to keep pushing the boundaries of flare.

Pinel was now a minor celebrity in the bowling world and much in demand as a speaker and teacher. His pronouncements, often delivered with an edge that could be interpreted as arrogance, could be grating. “I don’t know if I’d go so far as to say you either love him or you hate him,” says Neil Stremmel, the former USBC official. “I think it’s more you either love him or you, you know, keep him at a distance [because you] don’t understand him.”

Victor Marion is one of several bowling industry figures whom Pinel irritated. In 2006, Marion attended a Pinel-led seminar at a Las Vegas conference for pro shop owners. “He was writing some physics on the board, and he had it wrong,” recalls Marion, who had studied the topic as a hobby in school. “And I called him out. I was like, ‘Hey, Mo, I think you forgot a step there. You skipped some variables and didn’t do a couple of things.’ And he yelled at me, like, ‘Who’s teaching this class?’” Marion claims that a slightly intoxicated Pinel berated him for being a know-it-all, then ordered him to pipe down when one of his colleagues confirmed the mathematical error. (Marion eventually became a ball designer himself and now runs his own company, Big Bowling, in Spokane, Washington.)

Pinel also formed a bitter rivalry with a designer named Richie Sposato, a former pro bowler. In the late 1980s, around the same time that Pinel was refining his hypothesis about how core shape influences motion, Sposato went to a fateful Pink Floyd laser light show in Syracuse, New York. “I came home and I was really intrigued by these lasers,” he says. “And I just wanted to draw these lasers. And so I drew this diamond, and this light bulb went off in my head. It was like an aha moment—like, bingo, this is the perfect shape for a bowling ball.”

Sposato patented his diamond-shaped core, which he claims produces 20 percent more inertia than any competitor, and placed it in balls that he manufactured under the brand name Lane #1. But while he’s adamant that his core is the most advanced on the market, Sposato has always lagged behind Pinel in terms of sales and recognition. That dynamic led to years of conflict between the two ornery men. After one tussle in the online forum Bowling Ball Exchange, Pinel was banned for his caustic replies to Sposato’s criticism.

“See, Mo, he talks above everybody, talks down to people,” Sposato says. “People can’t understand what he’s talking about—physics-wise, all these big words, stuff like that. So they just look at him and they agree with him. But I can see right through it. I know what he’s talking about, what he’s saying, and I can always throw it right back in his face.” (In addition to designing Lane #1 balls, Sposato also owns a nightclub in Syracuse; he made headlines last year for openly flouting the state’s lockdown by hosting a party.)

Sposato was partially vindicated when MoRich flamed out. The company suffered from typical startup woes, notably maintaining quality control when dealing with contract factories. More fundamentally, demand was down. Between 1996 and 2006, the number of league bowlers—the folks willing to splash out for a new ball or three every year—decreased by 36 percent. But Pinel’s ideas had also been copied by bigger competitors, who were now touting audaciously asymmetric balls of their own. Unlike MoRich, those companies had the means to put their products into the hands of the most influential pros. (Getting a brand approved for use on the Professional Bowlers Association Tour, the sport’s top circuit, costs in excess of $100,000 in certification fees.)

Pinel kept sinking his dwindling savings into MoRich until 2011. Shortly thereafter, he was offered a lifeline by an old friend. Phil Cardinale, the man who’d given Pinel his first design opportunity for Track more than two decades earlier, had recently become the CEO of Radical Bowling, a niche ball brand owned by Brunswick Bowling. Cardinale and the VP of Brunswick Bowling invited Pinel to become Radical’s technology director. In addition to designing cores for the brand, Pinel became Radical’s chief ambassador. His #MoMonday YouTube series drew thousands of viewers every week, and he also scheduled more than a hundred personal appearances a year. Though in his seventies, Pinel would regularly put 45,000 miles a year on his black 2006 Chevy Malibu Maxx. He’d drive across the Dakotas in midwinter, dropping into tiny alleys to talk up the cores he’d designed for Radical, balls with names like the Ludicrous, the Katana Legend, and the Conspiracy Theory.

Pinel was still trying to maximize flare potential in his designs, an effort that was arguably becoming outmoded. A new generation of pro bowlers, both stronger and more technically sophisticated than their predecessors, have achieved unprecedented amounts of spin on their balls—sometimes as much as 600 revolutions per minute for those who opt for the increasingly popular two-handed throwing technique. Such bowlers don’t need as much hook assistance as in days gone by, so they’re using more stable balls—a strategic trend that may be having a trickle-down effect on the league bowlers who worship the sport’s stars.

In our conversations, Pinel never displayed any hint that he was worried about the future of his cores. He seemed grateful to still have a place in the industry, and he was happy to be on the road preaching about the intricate relationship between core design and ball motion. When we spoke in mid-February, he called from Fort Myers. His upcoming Southern-tour itinerary sounded brutal: Two more stops in Florida, then he’d be hitting pro shops in Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Memphis, Nashville, and Louisville. At the trip’s conclusion, he was slated to help announce the release of Radical’s newest balls, the Incognito Pearl and the Pandemonium Solid, which promises “a strong mid-lane motion and lots of continuation through the pin deck.”

Pinel did admit that his travels could be taxing on his creaky knees, but he otherwise expressed delight at his fantastic health. He said he had low blood pressure and, more important, excellent genes that he’d inherited from a grandmother who lived until 99. He affirmed that he had no plans to retire anytime soon. “I’m just an old man having a good time,” he told me. “I’m a kid in the street having a good time. I’m a hot rodder that happens to be a 78-year-old hot rodder.”

A FEW DAYS after that conversation, I called Pinel to ask yet another batch of follow-up questions; I had recently finished reviewing a 385-slide PowerPoint presentation that he’d shared, and I needed help processing some of the concepts. When my voicemail went unanswered after a few days, I tried again, and then again, and again. I emailed and texted, too, all to no avail. I worried that Pinel had heard that I’d spoken to Richie Sposato, his sworn enemy, and that he was giving me the silent treatment as a result.

On March 2, I received a call from a man named Paul Ridenour, a colleague of Pinel’s at Radical. He had upsetting news: Pinel had fallen ill while on the road and was now in a Baton Rouge hospital, where he’d been diagnosed with Covid-19. After he was admitted, the doctors had discovered that he had previously undiagnosed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The slow-moving cancer made him a high-risk Covid patient, and he’d gone through a rough patch in the ICU. But he was now improving. Ridenour assured me that Pinel would get in touch as soon as he was able—hopefully within a week, given the encouraging trajectory of his recovery.

Three days later, an email from Ronald Hickland arrived in my inbox. I’d spoken with him a month earlier, when he told me the story of having his life changed by Pinel at the Super Hoinke in 1993. Hickland was no longer a ball designer, having left the manufacturing side of the industry in 2015—a decision that, by his estimation, had reduced the number of full-time ball designers in the world to a mere four or five.

His email consisted of just two staggering sentences: “I’m not sure if you knew this or not but Mo passed away. He was the reason I got into bowling ball design.”

Pinel, like so many other Covid-19 patients, had fallen victim to a cytokine storm: His immune system had been duped into releasing too much of a certain protein that then overwhelmed his body and caused massive organ failure. His wife and one of his three adult sons had made it to Baton Rouge just in time to be by his side as he passed.

Pinel received no obituaries of note in the mainstream press. But there was a mighty outpouring of grief for Mo from bowling aficionados when the death was announced on Pinel’s Facebook fan page:

You were a genius at your craft and will be missed.

Thank you for all that you taught me about why bowling balls do what they do.

He was truly a giant in the bowling world and nobody will ever eclipse his achievements to modernize the sport.

Most of my life’s memories and stories that make me smile all come from the door that Mo creatively opened for me decades ago.

We lost a legend, a scientist, and a brilliant man. Mo, may you build that perfect ball in the afterlife.

But the Facebook eulogy that stayed with me the most was one that seemed to grapple with the uncertainty of Pinel’s legacy. “Hopefully the knowledge of ball motion from this man that was passed on is retained by those he taught,” the mourner wrote, “and his memory will live on.”

Pinel dedicated a fair portion of his life to disseminating his ideas, and he left behind artifacts such as his YouTube videos that will forever serve as repositories of his eccentric wisdom. But there was so much he never managed to articulate, so much teaching he still had left to do. And because he operated in a field that withered a great deal during his decades of involvement, there is perhaps no one left with his breadth of experience nor his bone-deep sense of bowling’s elemental splendor.

This is what the mercilessness of the pandemic has abruptly robbed from us: tens of thousands of men and women whose rare and hard-won knowledge can never be replicated. This is how artisanal skills are forgotten, how dialects vanish, how the stories meant to sustain us ebb away from our collective memory. And it’s all happening at a pace far faster than we can grieve.

After meditating on all that’s been lost, I could come up with only one fitting way to honor what Mo’s time here meant. As I write these words, I stand precisely 12 days away from being fully vaccinated against the coronavirus. I plan to celebrate by taking my kids bowling.

Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at [email protected].

I have been bowling since I could walk. One day I received a bowling magazine (Bowling This Month or Bowlers Digest) that had all kinds of core designs on the front cover. I then began to draw core designs whenever one would pop into my head. It was easy to just draw something when you don’t have to worry about failure rates, and RG/Diff numbers. When I was finished high school, I traveled to San Antonio, TX for an informational interview with Columbia 300 and Track. After that interview, I became so discouraged with becoming a core design, that I just turned my attentions to working around bowling. I was around for Mo’s first core. Mo’s first core was the Track Shark. With the success of the Shark, AMF lured Mo away to design the Sumo (very similar shape to the Shark for its time) with the incentives.

As I am sure you have found in your research there is a lot of learning still to be done in core design and ball motion. Bowling Ball drill sheets continue to push outdated information, and thinking. When you have just a few companies left, it is hard to find enough resources to continue to push things. USBC continues to limit cores in general. Continuing to go backwards with technology.

My feeling is that core designs aren’t the problem with the scoring environment in bowling. It is the lane conditions that bowlers are now allowed to bowl on. A 300 was something only the better bowlers could achieve in the 1960 through 80s. There was one 900 series in the sport, and that was unsanctioned. With automatic lane conditioning machine, lane maintenance became a lot easier. When lane dressing machines became affordable, bowling centers were able to dress the lanes whenever they wished. There became “normal” lane patterns, not just some random pattern put out by the lane man once a week, or once every other week with a bug sprayer. Think about if you went and bowl at your local center after a week of open play and league bowling, how well would you score?

Back to core designs, I am sure you have done a lot of research. Mo took up the Front Man position when it came to talking about core design. Ray Edwards of Brunswick has been designing revolutionary cores for many years, including the Brunswick Phantom series which caused ABC/USBC to design standards for bowling balls. There are many others that have designed cores that have remained in the shadows. Mo’s company held several patients which affected the advancement of core design until those patients expired. Storm made the Crux core design and Mo sued them and received some kind of settlement. The Crux core was only used again after this matter was settled.

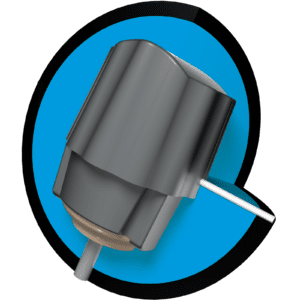

Mo also helped design a tool to help pro shop’s easily find a bowler’s axis point. The AMF Armadillo is still a standard in the industry.

Mo also had a hand in creating a Determinator with helps locate the Z axis of an Asymmetrical bowling ball. (I think Jayhawk could provide more detail on this machine, and it is sold through them)

One of the most revolutionary things Mo created was the Dual Angle Layout system for laying out Asymmetrical bowling balls. Look at drill sheets before, and after.

I could give a lot more detail about the Dual Angle system, but I am sure you have read enough.

Great article, and I love the bowling industry, and I hope that more companies, families, organizations will become passionite about bowling again, and the sport will grow again.

I have a feeling with over 100 bowling centers closing due to Covid, that Bowlmor will become the party center company throughout the US. With the surplus of used lane equipment, a lot of small 12-24 lane center will open that will be privately owned and have owners that love the sport and want it to grow again.

[“What he did was he helped to bring asymmetry into a better understanding,” says Ronald Hickland, the teenage Pinel fan who went on to design more than 400 balls for Ebonite International.]

Is that number correct? Ronald Hickland is credited with designing 400 bowling balls?

Great article Mo truly was a genius.